Only you can stop confirmation bias

Confirmation bias leads us to hold false belief with a confidence greater than evidence can justify. Curbing it when making decisions requires patience and rigor. It's a battle that's worth the effort.

A while back I volunteered to contribute to a book on the behaviours and history of political, legal, and socio-economic systems. It was to be a primer for people creating products with the potential to disrupt those systems. My contribution was a chapter on confirmation bias, detailing its effects, its workings, and how it can be overcome. Though the book was never published, my research had me reconsidering my behaviour. Always careful with my words, I started speaking even more purposefully, not wanting to pass bias on to others. The experience had such an impact that I couldn't let my chapter sit unread, and split it into three articles. The first speaks to the pernicious influence of confirmation bias, while the second describes how it grows and spreads. This is the last in the series, explaining what we can do to fight confirmation bias.

If you've been following this series on confirmation bias or already know its mechanisms, you may be feeling a little wary of your internal state of the world. I know I was during my research. It's alarming to know that we can gather false truths, nurture them through selective testing and interpretation, and become certain they are true, all while thinking we're being perfectly reasonable. All is not lost, however. There are ways we can fight our bias and lessen its impact — you may already be using some of them. Groups are also prone to biased decision-making, and there are techniques for lessening this error as well. As for debiasing others, that can be a touch more complicated.

Entrenched in our brains, confirmation bias seems difficult to combat. Though we may never be free of our biases, we can try to make sure our decisions and actions remain untainted. As you probably realize, this isn't easy. Working against stereotypes — a product of confirmation bias — for instance, takes more time and uses different parts of our brains than our natural thought processes. It's a battle worth fighting. Bias affects decisions both big and small — like hiring a new employee, crossing the street to avoid someone, or even the words we use to describe others. Actions based on bias can have long-term consequences, such as an educator forming opinions of their students based on where they live, as mentioned in part one of this series.

The good news is that at times we unknowingly reduce bias' impact on our decision-making. If we feel we might suffer a loss of status for a biased decision, our desire for approval can help lessen bias. On the other hand, there's little evidence that incentives — such as a reward for considering every course of action — improve the reliability of our decision-making. We can't simply ask and expect ourselves and others to "try harder." Doing so assumes we already know effective strategies and somehow aren't using them properly. In many cases, incentives can produce worse outcomes. A financial advisor with fees tied to an increase in portfolio value, for example, might be biased towards riskier trades.

We also unknowingly lessen our bias in decisions where our accountability is at stake, provided we have the appropriate decision-making strategies. Even for those limited to experience in a related field, accountability can be better than punishments and incentives at countering bias. We have a strong social need for consistency. When making decisions for which we'll be held accountable, we're willing to put in the effort and more effectively use information. Generally, we want to avoid embarrassment and maintain pride. This means we're more likely to preemptively self-criticise and foresee flaws. That thirst for accountability can go too far, however. We sometimes feel a need to "give people what they want", particularly if we're undecided — like fudging a report to match expectations.

| Is that a predator's face I think I see? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| That's actually a predator's face | Yes | True positive | False negative may result in death |

| No | False positive results in fleeing unnecessarily | True negative | |

Along with accountability, context is also key when unknowingly making decisions with less bias. With some decisions, such as those related to survival, false negative errors have a higher cost (see Fig. 1). Others may have expensive false positive errors. It helps to have experience in the area under study, especially if we encounter a problem we've solved before. When we encounter these high-cost conditions, we usually err on the side of caution. Yet confirmation bias often reappears if we try to map that experience to a different domain. One example might be a successful day-trader confidently wading into socio-economic theory with a selective knowledge in that field.

It's reassuring that we unknowingly reduce our bias when making certain decisions. What can be done to improve that intuition? In part two of this series we learned that confirmation bias can often develop if we fail to properly apply formal reasoning. We might have some basic logic, economics, or statistics knowledge — such as sampling — but may not know when or even how to use it. For example, people often misinterpret or misuse summary statistics like mean, median, or standard deviation (see Fig. 2), and could benefit from refresher training. A lesson on how causation and correlation are frequently conflated could also help. There is evidence that short training sessions in a domain with which we're comfortable — sports statistics, for instance — can help reduce bias in other areas. That assist, however, often diminishes after only two weeks and suffers when learning complex rules, like Bayes theorem.

In part one of this series we learned of a 2013 "study of studies" on gender and risk which showed that even scholars and experts can be victims of bias. There seems to be no guarantee that intuition can be improved with more education. Outside motivation — punishment, accountability, etc. — isn't always helpful, and can sometimes have the opposite effect, like taking accountability too far and delivering what's expected. We can't debias ourselves by ourselves, as we're likely biased against even the existence of our biases. How can we hope to lessen their impact? Formal approaches exist but are more geared towards reducing bias in group decisions. As it turns out, simply knowing that confirmation bias exists goes a long way. A basic understanding of how unreliable human reasoning can be, with no instructions other than "beware", can help counter biases. The best strategy to exceed this bare minimum, however, may be to consider the opposite.

If you've ever argued a position in school — in English or a debate class, perhaps — you may have prepared by researching opposing arguments. Considering the opposite is also a decent strategy for fighting bias in our beliefs. This might be as simple as asking ourselves how we could be wrong on a position, why, and for what reasons. In doing so, we widen our search and direct our attention to contrary evidence. This approach can help reduce overconfidence, a symptom of confirmation bias. It's also been shown to lessen bias when seeking and interpreting new information. We also reason better with two theories than when evaluating a single hypothesis. What's important is that we seriously examine a specific opposing belief.

Naturally, seriously examining an alternate belief is the key. We might not give an opposing belief its due, especially if we feel ours is already viable. Although paying attention to contrary evidence can help counter bias, requiring too many opposing views can backfire. Failing to come up with a required number of alternate theories might make us consider weaker ones, making us more confident in our own viewpoint. Considering more than one theory at once can also divide our attention. We're then less likely to give other theories their due. Instead, think about alternates separately and independently.

We might be able to hold our confirmation bias at bay so long as we're aware of it, and give serious thought to viewpoints opposed to our own. What about people we work with, or our friends and family?

Unfortunately, when it comes to other individuals, we may just have to grin and bear it. In the absence of bias, a rational person could correct their belief with more information. With bias, more information is not better. Trying to convince someone affected by confirmation bias to change their belief may have the opposite effect and increase their leanings. This is known as the backfire effect or belief perseverance. Giving the same ambiguous information to people with differing beliefs may move their beliefs further apart. Depending on their viewpoint, two people may see the same evidence and interpret it differently, judging it as being more consistent with their bias.

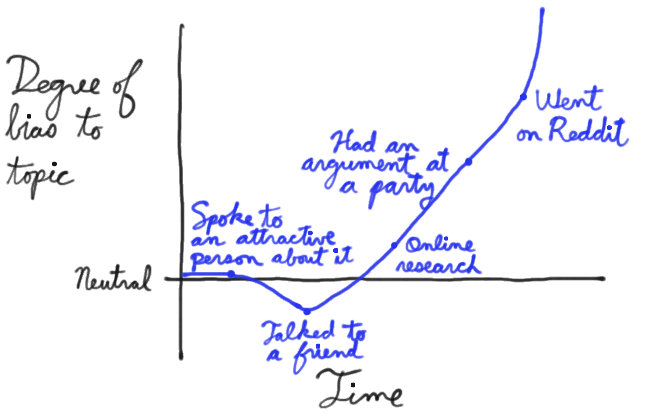

Considering belief formation as a series of signals, as in part two of this series, can also show how difficult it may be to debias someone else. The effect of each signal depends on those which came before it, including any prior beliefs (see Fig. 3). To debias someone, we may need to know their initial belief on a topic as well as the order of signals which followed. Unraveling how they nurtured this false knowledge takes care, understanding, and respect. It also depends on open and reliable narrators with good memories and an interest in reaching the truth. With severe bias, our efforts to reason away another's false belief could be futile. This is perfectly illustrated by The Doobie Brothers in "What a Fool Believes":

But what a fool believes he sees

No wise man has the power to reason away

What seems to be

Is always better than nothing

Than nothing at all

Our friends and family with severe bias may be lost to it, but our workplace can still be saved. Thankfully, many decisions which matter are made by groups, which are more readily debiased than individuals. Many tried and tested strategies for lessening bias in groups exist, usually involving a framework or tool to help make sound decisions. Groups can make use of decision aids, information displays, statistical models, and other formal decision analysis techniques. Complex problems can be split into smaller, simpler ones — such as listing the pros and cons of a position — and assigned to smaller groups. These technical strategies are simply out of reach for most individuals. Whereas individuals can introduce bias at every step of the decision-making process, groups can track their progress and use the results as feedback.

When using strategies or tools to make unbiased decisions at work, adoption can be difficult. Processes like these are usually imposed company-wide from the top down, and as such are often rejected or begrudgingly implemented, leading to failure. A bottom-up approach can have better results than a general process imposed from the top-down. When those making the decisions choose a strategy appropriate to their group, their sense of ownership helps them stick with it and approach it more honestly. If it works for them, the group can evangelise the strategy and inspire adoption. Beware, however. As with ourselves, groups can also underestimate their bias and be overconfident in their decision-making. They, like us, may fail to recognize a need for help.

Groups are also prone to group-think. Their members may be influenced by others with either more seniority, or who are more aggressively persuasive. Because of this, groups may anchor on the judgments of a few people. Having group members think about their preferences and estimates before a meeting can help lessen this risk. Strategies and tools such as multi-attribute analysis, or decision support systems prompt groups to think more deeply than otherwise, and can also check for errors in the decision-making process. It's also a good idea to maintain complementary expertise within the group, and be aware of blind spots due to shared errors. A supportive environment in which everyone feels free to correct belief or adjust decisions is also key.

Group-think due to blind spots can be lessened through diversity of experience within the group. While training can help preserve that diversity of perspectives, groups can do better by increasing the sample size of experience. Drawing people in from a wider community increases diversity of experience and, in turn, increases diversity of thought. To reduce the risk of locally-held beliefs, groups should include members of differing genders, ethnicities, nationalities, racial identities, and socioeconomic classes.

Fighting confirmation bias in ourselves and in groups requires careful and consistent attention to how we make decisions. The solutions are there:

- At a bare minimum, know that bias exists and is widespread.

- Consider opposing arguments or alternate theories to those which drive your actions.

- Use tools and decision-making frameworks when you collaborate at work.

- Involve people with different backgrounds and experiences to rein in group-think.

My research in confirmation bias had a profound impact on me. I was aware of it, but I had no idea how often our brains fail to be rational. It made me wonder which biases I had adopted, from where, and how much they had affected my actions. What bothered me the most was the possibility of spreading false belief to others. I vowed that bias would stop with me. Anything I was unsure of remained unsaid or came with a disclaimer. I tried to limit my use of words like "every" or "none" when I really meant "most" or "few". More importantly, I better understood how others could become so firmly attached to false belief or prejudice in spite of themselves, and how the slightest action borne of that bias could negatively affect others in a big way. I started to imagine a world free from the effects of bias, and it was glorious. What will you do to help make that world a reality?

References

- [KLAYMAN1995] Klayman, J. (1995). Varieties of confirmation bias. In J. Busemeyer, R. Hastie, & D. L. Medin (Eds.), Decision making from a cognitive perspective. New York: Academic Press (Psychology of Learning and Motivation, vol. 32), pp. 365-418.

- [LARRICK2004] Larrick, R. P. (2004). Debiasing, in Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making (eds D. J. Koehler and N. Harvey), Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Malden, MA, USA.

- [NELSON2015] Nelson, J. A. (2015). Are women really more risk-averse than men? A re-analysis of the literature using expanded methods. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29: 566-585.

- [NICKERSON1998] Nickerson, J. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: a ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 175-220.

- [RABIN1999] Rabin, Matthew and Schrag, Joel L. (1999). First Impressions Matter: A Model of Confirmatory Bias, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, issue 1, p. 37-82.