Three reasons why we make bad decisions, and why it matters

How our brain's tendency to selectively gather, interpret, and recall information makes us behave irrationally.

A while back I volunteered to contribute to a book on the behaviours and history of political, legal, and socio-economic systems. It was to be a primer for people creating products with the potential to disrupt those systems. My contribution was a chapter on confirmation bias, detailing its effects, its workings, and how it can be overcome. Though the book was never published, my research had me reconsidering my behaviour. Always careful with my words, I started speaking even more purposefully, not wanting to pass bias on to others. The experience had such an impact that I couldn't let my chapter sit unread, and split it into three articles. This is the first of the three, describing the pernicious influence of confirmation bias. The other two explain how it grows and spreads, and what we can do to fight it.

"THIS JUST IN: We're getting reports — around the world — of a disease rapidly spreading out of control. The infected are in the millions, and have started behaving irrationally. Some have been seen making poor judgments of their and others' ability. Girls as young as six with the disease are viewing women as less smart than men. Scientists are working on a cure, but a viable solution could be weeks away. In the meantime, everyone is urged to use caution."

Thankfully, this is not a real news story. The disease isn't real, but the symptoms are, and almost everyone on Earth is affected. If it were a disease, there might be a cure, or at least a way to slow the contagion. There isn't. It's us, or more specifically our brains.

You may know this affliction as confirmation bias, one of many cognitive or unconscious biases which affect how we reason. Unlike a leaning or a slant, like left- or right-wing bias, cognitive biases are the result of involuntary mental "short-cuts", leftovers from when we had to quickly tell friend from foe, or avoid potentially dangerous situations. These short-cuts may have kept our ancestors alive, but they impede logic and accuracy necessary in our modern world.

Before confirmation bias had a name, people were thought to be largely rational. An error in judgment was simply a matter of poor reasoning. In his recount of the Peloponnesian War almost 2500 years ago, historian Thucydides called it a "habit":

"… and their judgment was based more upon blind wishing than upon any sound prediction; for it is a habit of mankind to entrust to careless hope what they long for, and to use sovereign reason to thrust aside what they do not desire."

Over 400 years ago, Sir Francis Bacon was more inclined to consider this "habit" as a trick of the mind:

"The human understanding when it has once adopted an opinion […] draws all things else to support and agree with it. And though there be a greater number and weight of instances to be found on the other side, yet these it either neglects and despises, or else by some distinction sets aside and rejects, in order that […] its former conclusions may remain inviolate."

It wasn't until 1960, when psychologist Peter Wason performed his first selection experiment, that confirmation bias finally had a name.

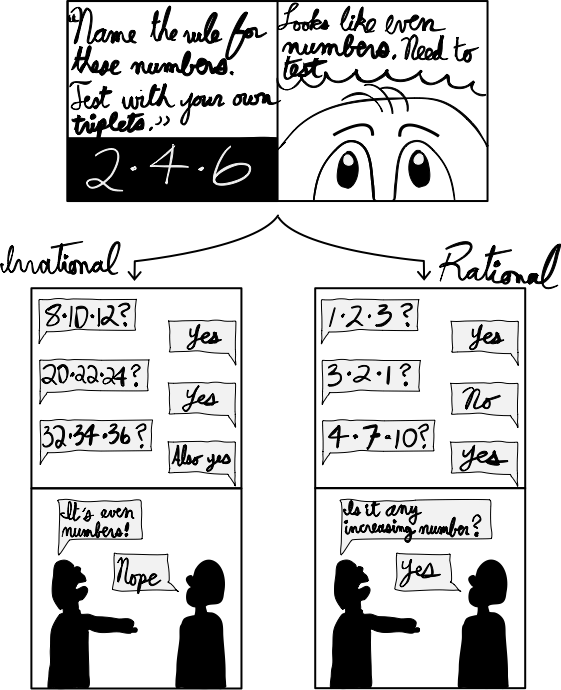

Wason's experiment was simple: present a person with three numbers (e.g. 2-4-6), and ask them to guess the rule for those numbers. That person was then directed to test their theory with their own triplets, and was told when each matched the actual rule. Participants mostly came up with rules specific to the initial triplet (e.g. "numbers increasing by two" in the case of 2-4-6), and only tested them with triplets which fit their theory (e.g. 9-11-13). They rarely chose triplets which didn't agree with their theory (e.g. 9-10-11). Most, then, never guessed the actual rule, which was always "any ascending sequence." Fig. 1 shows an example of the irrational approach most people took, as well as a rational one. One of the tendencies which supports confirmation bias involves improper selection of evidence.

Of the many cognitive biases, confirmation bias likely does us the most harm. It tricks us into accepting untruths and nurtures them until we're certain they're true. It leads us to hold false beliefs with a confidence greater than evidence can justify. Those affected will often misinterpret new information as supporting a previously-held but false belief. It may not seem dangerous, but confirmation bias can change the way we view reality.

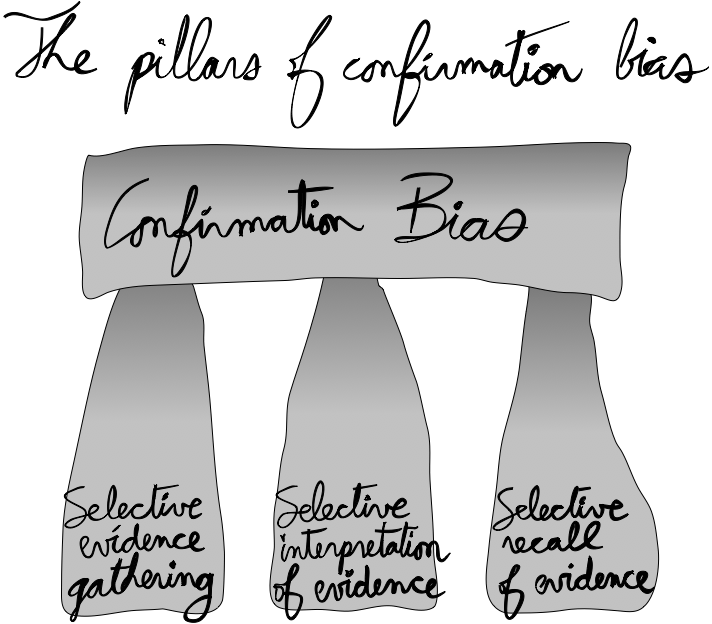

The Wason experiment demonstrated one tendency contributing to confirmation bias: selective evidence gathering. We may only see what our beliefs lead us to expect. We also have a tendency to selectively interpret evidence for or against a belief. We may add weight to information or events which support our theories, and discount information which does not. When it comes to remembering evidence, we tend to filter out or forget opposing views and their supporting facts, and selectively recall evidence which supports our views. These tendencies support confirmation bias (see Fig. 2) and lead to over-confidence in our beliefs. Over-confidence, in turn, can lead to bad choices, sometimes resulting in risky and extreme behaviour.

Horoscopes are a mild example of how confirmation bias can affect behaviour. Perhaps you know someone who, in some small way, has acted on the advice of a horoscope or a psychic. Such mediums remain popular largely because we want to believe them. To reinforce our belief, we tend to focus on or remember what we expect or want from them. We also more readily recall the times they were right, and forget or discount when they were wrong. Many "readings" also label the viewer as having positive traits, such as kindness and generosity. People often fail to consider how universal these traits are, and instead selectively use those readings as supporting credibility. This behaviour opens us to place faith in astrology, fortune-tellers, and con artists, who — knowingly or not — appeal to those traits so that we recognize ourselves in their "predictions".

This same tendency to see or remember what we expect or desire can also feed more serious conditions such as hypochondria and paranoia. Depressed people may also focus on information which strengthens their depression, and ignore more positive information which may help them. Over time, this selective memory can affect and reinforce their "core beliefs" — absolute truths we hold about ourselves — and lead to a negative self-image.

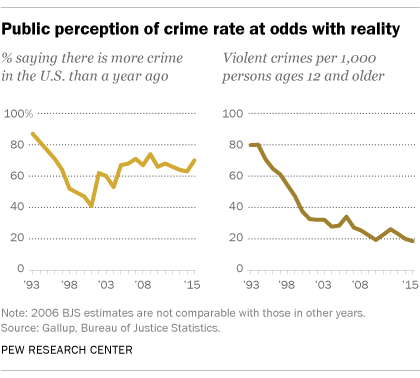

Tendencies contributing to confirmation bias can lead us to confidently make bad decisions which affect ourselves and others. Many people wrongly believe that crime is rising, and vote for candidates who are tougher on crime, despite the reality (see Fig. 3). Maybe you know someone — a friend or relative, perhaps — who seems to have nothing good to say about a particular group. Have they gone out of their way to avoid a member of that group? Or treated someone in that group differently than they would others? Such stereotypes and prejudices are largely fed by confirmation bias, and can influence how we treat or view "others" — people different from us.

Thanks to confirmation bias we may readily observe and recall unusual behaviours in people from distinct ethnicities. This selective evidence gathering and recall, left unchecked, can contribute to racist stereotypes. Belief due to tainted memory increases our confidence in stereotypes, leading us to more likely act on them. Several studies have shown how bias can change our reactions to people about whom we hold stereotypes — even if we are only told those people belong to a specific group.

In one such study, participants were shown a video of a girl playing. Half were told the girl's parents were college-educated with white-collar jobs. They were shown the girl playing in a well-to-do suburban neighbourhood. The other half was told the girl's parents were high-school graduates with blue-collar jobs, and were shown her playing in a disadvantaged urban neighbourhood. People in each of those groups were then shown the same video of the girl answering a series of questions, and were asked to evaluate her reading level. The group which was told the girl was from a well-to-do suburban family rated the girl's reading ability significantly higher than the group which was told she was from a poorer neighbourhood. Both groups saw the same Q&A video, were given no other information, yet reached different conclusions because of how they felt about where the girl lived. Consider what happens when caregivers and teachers approach their students with a similar bias.

This tendency to make biased decisions based on confidence in a stereotype isn't born of years of prejudicial thinking. In a similar study, 5-7 year-olds were told of a person who was "really, really smart." The children were then shown a picture of four adults — two women and two men — and were asked to pick the "really, really smart" one. At aged 5, boys and girls chose their own gender roughly equally. Girls aged 6 or 7, however, were significantly less likely than boys the same age to view their own gender positively. In another study with different children, boys and girls aged 6 or 7 were introduced to a game "only for kids who are really, really smart" or one "only for kids who try really, really hard." The girls were less interested than the boys in the game for "really, really smart" children, but not the game for "kids who try really, really hard."

Like Thucydides, we may feel our reasoning is stronger than others', that we never fall into the "habit" of misjudging people, especially a child in a video, so easily. Yet people who have studied reasoning and statistics can still have a problem with confirmation bias and stereotypes. As an example, numerous peer-reviewed studies claim to show that women are more risk-averse than men. A 2013 "study of studies", however, claims that those studies and their authors were likely affected by stereotypes induced by bias. The studies' authors reached inaccurate conclusions by falling prey to tendencies behind confirmation bias. Many inaccurately cited conclusions of earlier literature, or emphasized results agreeing with stereotypes, while downplaying or omitting results which did not. These confirming results were, in turn, more likely to be published. Researchers overlooked situations where women naturally take on a great deal of risk, such as with child birth or risk of domestic violence. Instead, areas of risk such as finance were studied and findings extrapolated to a broader context.

Since Wason's experiment, many studies have shown that not only do we hold cognitive biases, they can be difficult to correct. We're usually unaware of our own confirmation bias. Worse, although our reasoning about information may be biased, we still rationally apply that data to our own state of the world. We don't see our bias. We feel we're being reasonable, and we often are, but with skewed information. This bias-influenced reasoning may make sense to us, but it results in bad decisions. Ignorant to our bias, we may become over-confident in our beliefs and risk tainting future reasoning, thereby reinforcing our bias.

Confirmation bias exists and negatively influences human behaviour — so now what? We can correct our own bias, although it can be difficult. Awareness helps a great deal, as it turns out. There are also habits we can pick up to better keep our bias in check. That's in part three of this series. Our next step is to gain a better understanding of how confirmation bias grows and spreads, which brings us to part two.

References

- [BIAN2017] Bian, L., Leslie, S., and Cimpian, A. (2017). Gender stereotypes about intellectual ability emerge early and influence children’s interests. Science, 27 Jan 2017, Vol. 355, Issue 6323, pp. 389-391.

- [JONES2000] Jones, M., and Sugden, R. (2000). Positive confirmation bias in the acquisition of information. (Dundee Discussion Papers in Economics; No. 115). University of Dundee.

- [LARRICK2004] Larrick, R. P. (2004). Debiasing, in Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making (eds D. J. Koehler and N. Harvey), Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Malden, MA, USA.

- [NELSON2015] Nelson, J. A. (2015). Are women really more risk-averse than men? A re-analysis of the literature using expanded methods. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29: 566-585.

- [NICKERSON1998] Nickerson, J. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: a ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 175-220.

- [RABIN1999] Rabin, Matthew and Schrag, Joel L. (1999). First Impressions Matter: A Model of Confirmatory Bias, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, issue 1, p. 37-82.