How the "holy grail" of realtime computer graphics will change home entertainment

Video games, virtual reality, and augmented reality will appear more lifelike and naturally lit thanks to new realtime raytracing chips and consoles. I also revisit an old scene created [mumble-mumble] years ago in POV-Ray.

Digital gaming and home entertainment is about to get real … well, more real, not really real. Computer-generated scenes have grown increasingly realistic, thanks largely to faster hardware. Though recent games and demos resemble reality, they subtly fake it by taking advantage of optimizations and shortcuts. With closer scrutiny, lighting, shadows, and reflections can appear slightly off. These scenes lack photorealism, the decades-long "holy grail" of computer graphics.

That holy grail of photorealistic game play is now within our grasp. NVIDIA and AMD will ship graphics processors supporting realtime raytracing later this year, with Sony and Microsoft leveraging their capabilities in new Playstation, Xbox, and Windows releases.

Since 1980, raytracing has been the best promise for photorealism in computer graphics. The technique involves following (or tracing) rays of light as they leave a light source and interact with the scene. That light bounces off many surfaces, each with their own reflective or absorption capabilities. At every collision, the raytracing algorithm calculates changes in that ray of light and adjusts accordingly before it's finally projected onto the resulting 2-dimensional image.

As you can imagine, raytracing is extremely intensive, often taking hours for a single frame. That hasn't stopped it from being used in movies and video, where post-production takes months. Realtime raytracing, though, opens up new possibilities. Instead of watching actors in front of a green screen, a director can watch them in a photorealistic scene live on a monitor. With realtime raytracing on a chip, movie crews with even the smallest budgets will be able to track a complete scene while filming.

If you're an avid gamer, realtime raytracing will bring an improved look to many of your games. The biggest impact will likely be in VR, offering increasingly immersive environments. Eventually your phone will support realtime raytracing, resulting in more natural interactions with AR objects and real-world lighting. A coffee table previewed in your living room will look so real you might be tempted to put your mug on it.

All this thinking about raytracing reminded me of high-school and university when I played around with POV-Ray, an open source raytracer with its own scene description language. Simple scenes took several minutes to render. More complex scenes required more computing power than I could muster.

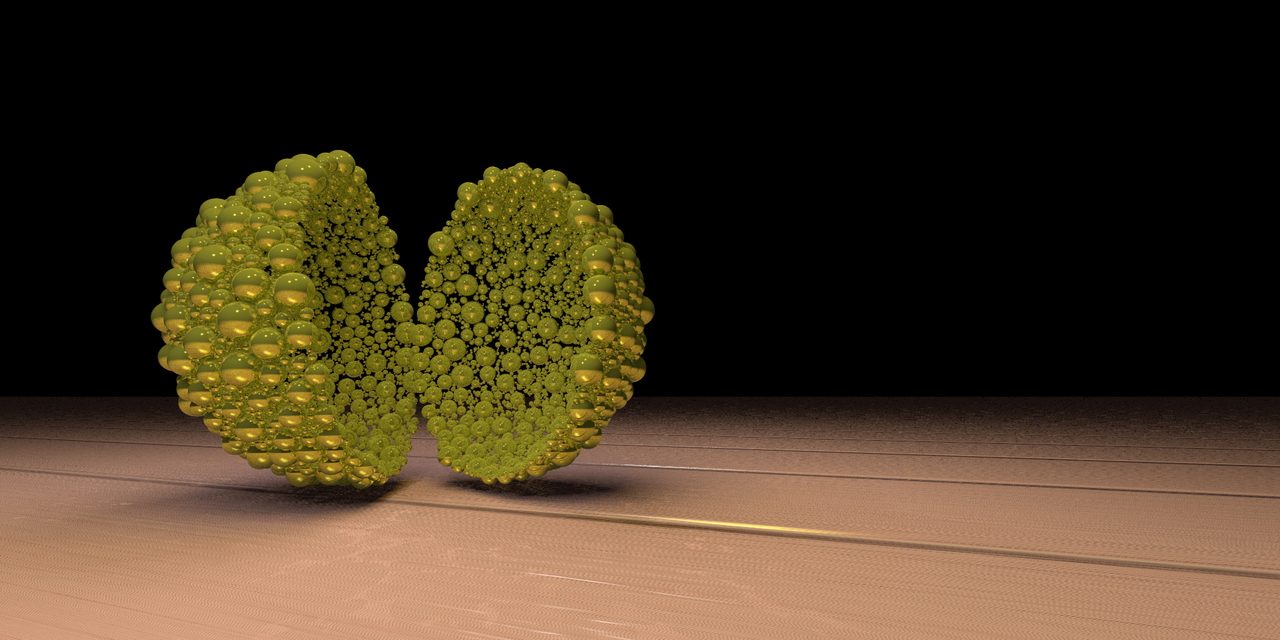

I dug up some of my old POV-Ray files to see if I could render them today. What I found was an old QuickBASIC program generating 1500+ random spheres connected in a sphere shape. I remember being able to draw a portion of that scene, but not much else. Luckily there's a free QB interpreter and editor for Mac OS. Within a few minutes I had the scene:

The scene took only seconds to render, so I decided to double the number of spheres, position the camera and some lights, specify a plane, and add some colour. It didn't take much time to render the resulting image:

It looks like the sphere I was drawing was actually a half-sphere. This might have been an old optimization on my part. Rather than fix it, I decided to make it a feature. I re-used the same object, then rotated and translated the half-spheres to appear as if it was a sphere opened to the camera:

To polish up the image, I adjusted the light sources, colours, and textures. My goal was for the scene to look like a gold piece on a wooden plane:

If I were to start this project from scratch today, I obviously wouldn't use QuickBASIC. Instead, I would use Vapory, POV-Ray bindings for Python, to render the scene without generating a scene file. It was fun to revisit POV-Ray after so many years, and I'll likely come back to it soon.